More Information

Submitted: February 02, 2024 | Approved: February 16, 2024 | Published: February 19, 2024

How to cite this article: Shin MK, Tshimbombu TN. Strengthening Healthcare Delivery in the Democratic Republic of Congo through Adequate Nursing Workforce. Clin J Nurs Care Pract. 2024; 8: 007-010.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.cjncp.1001051

Copyright License: © 2024 Shin MK, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Nursing shortage; Healthcare disparities; Conflict zones; Resource allocation; Health policy reform

Strengthening Healthcare Delivery in the Democratic Republic of Congo through Adequate Nursing Workforce

Min Kyung Shin1 and Tshibambe N Tshimbombu2*

1University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada, USA

2Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, 1 Rope Ferry Rd, Hanover, NH 03755, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Tshibambe N Tshimbombu, BA, Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine, 246 Fairview St, Fairlee VT 05045, Apt#1, USA, Email: [email protected]

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) grapples with a critical shortage of nurses, exacerbating disparities in healthcare access and outcomes. This mini-review examines the factors impacting the nursing workforce in the DRC and presents potential solutions to strengthen it. Decades-long regional conflicts have endangered the nursing workforce, resulting in an imbalanced distribution that disproportionately favors urban areas over rural regions. Inadequate healthcare funding, compounded by mismanagement, has led to resource scarcity and inequitable distribution, further hampering nursing efforts. Additionally, stagnant policy reforms and ineffective advocacy have hindered improvements in nurse employment, wages, education, and working conditions. Infrastructure deficiencies and medical supply shortages have also contributed to reduced incentives for nursing professionals. Therefore, we undertook a mini-review aimed at offering a succinct and targeted overview of nursing care in the DRC. This involved analyzing available literature and data concerning the nursing workforce with a particular focus on the DRC. We believe that addressing these interlinked challenges necessitates comprehensive strategies that prioritize establishing regional stability, responsibly allocating and increasing healthcare funding, incentivizing nurse recruitment and retention through policy adjustments, enhancing healthcare infrastructure and nursing education, and fostering both local and global collaboration. Investing in nursing is paramount for transforming healthcare delivery in the DRC, particularly considering nurses' pivotal roles in delivering preventive, therapeutic, and palliative care services. Strengthening nursing capacity and addressing systemic challenges are essential steps toward mitigating healthcare disparities and enhancing population health, aligning with the objectives outlined in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

According to the World Health Organization's Sustainable Development Goal 3, aimed at Health and Well-being, there is a pressing need for an additional 9 million nurses and midwives by the year 2030 [1]. Effectively meeting this demand entails adopting the "leave no one behind" [2,3] principle and giving priority to evidence-based competency educational programs and policies addressing local hurdles aimed at improving nursing practice as proposed by the WHO [2,4,5].

The needs identified by the WHO are particularly pressing in resource-constrained environments such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where achieving such a target can seem insurmountable due to the myriad challenges plaguing the local healthcare system. These challenges include a scarcity of skilled healthcare professionals and limited access to quality care, particularly in rural and underserved regions [6].

Currently, nurses comprise 45% of the DRC’s healthcare workforce with a significantly higher concentration in urban areas, notably in the capital city of Kinshasa [7]. Given the nation’s large population (~112 million) of whom only a fraction (~14 million) resides in Kinshasa, the disparity in nursing coverage widens the gap in healthcare accessibility. Factors propelling rural-urban migration stem from decades of enduring military conflicts and ongoing political instability, resulting in severe damage to the nation's economy, infrastructure, and human resources [6]. Consequently, urban areas harbor a significant portion of the nursing workforce, while rural clinics - mostly under-resources - struggle to accommodate and employ all available nurses.

In clinical settings, nurses heavily rely on the Object-Based Methodology (OBM), characterized by hands-on learning that integrates active and experiential learning models alongside constructivist theories of knowledge acquisition [2]. Nonetheless, empirical research validates the efficacy of Competency-Based Practice (CBP) in the DRC within clinical environments. CBP involves a structured approach to education, assessment, feedback, and self-reflection, allowing professionals to demonstrate proficiency in expected competencies [2]. Congolese nurses have experienced significant benefits from CBP, resulting in improvements in professional communication, decision-making, and healthcare interventions [2]. Despite its acknowledged effectiveness, the integration of CBP into clinical practice in the DRC remains pending.

All the above variables have resulted in a current healthcare landscape where nurses are undervalued, inadequately trained, and striving to provide essential care to complex and diverse medical needs whilst balancing the complexities and deficiencies of the healthcare system. This mini-review will outline the detrimental factors hindering progress toward the WHO goal and propose pathways to transform ongoing local challenges into more manageable hurdles. While we acknowledge that some of our proposed pathways might be beneficial to other low-income countries, our primary aim is to concentrate on enhancements that specifically tackle the challenges unique to the DRC.

Role of nurses in DRC healthcare delivery

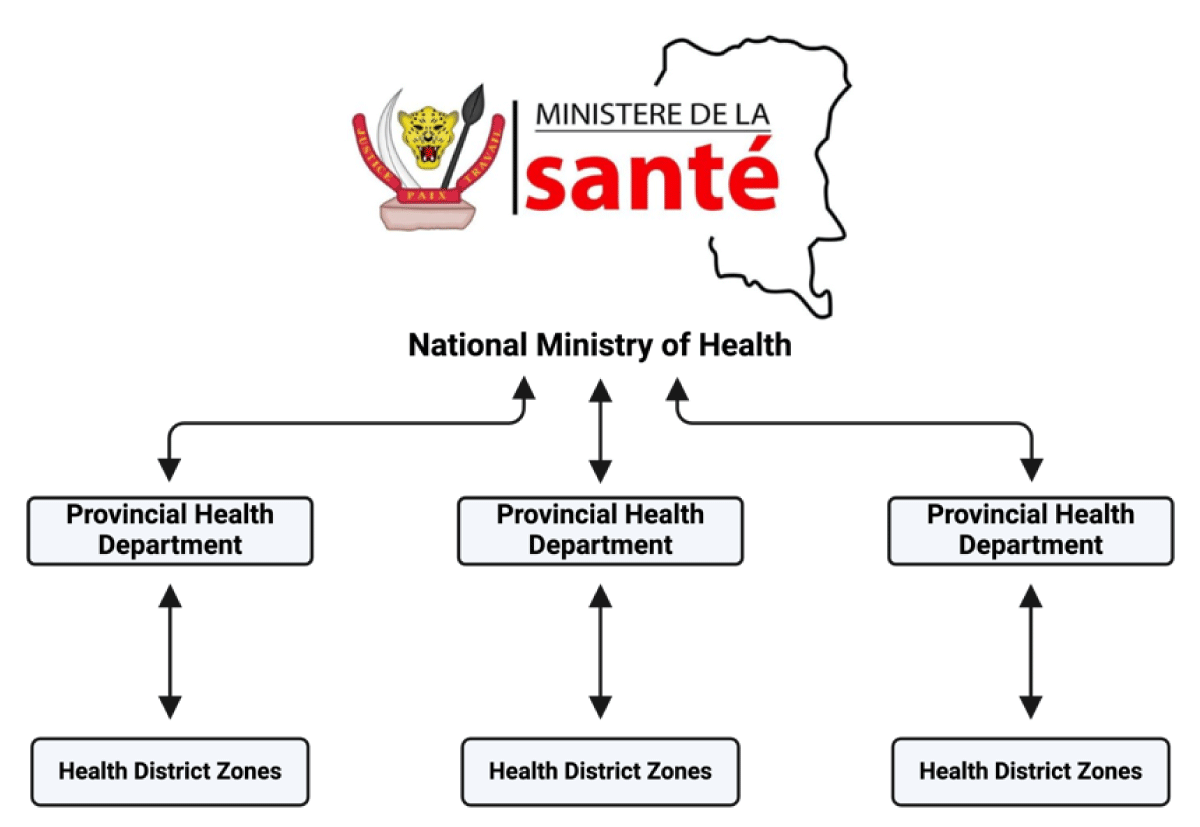

The health system in the DRC follows a pyramidal structure [7] (Figure 1), comprising three main units overseen by different levels of authority. At the top is the National Ministry of Health, which provides leadership and direction for healthcare policies and programs. The intermediate level is managed by regional health departments, responsible for overseeing programs within health district zones. These zones constitute the operational unit, where healthcare services are delivered directly to the end user (i.e. the populace). Nurses are primarily stationed at health centers, which typically consist of an advanced provider such as a physician at the primary level, and a practicing or trained nurse at the secondary level, then other hospital staff [7].

Figure 1: Organization of the healthcare system in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Traditionally, nurses in this system serve as frontline healthcare personnel, offering preventive care, health promotion, disease management, and patient education. The substantial impact of nursing interventions on patient outcomes is intuitive and well-established with specific benefits in decreased mortality rates, improved treatment adherence, and enhanced quality of life [8,9]. The DRC’s local challenges have curtailed nurse recruitment, training, and retention, posing significant barriers to improving nursing practice across the country. Addressing these challenges is imperative for enhancing the quality and effectiveness of the nursing workforce nationwide.

Factors impacting adequate nursing training and practice

Lack of regional safety: For more than three decades, the DRC has been mired in prolonged internal armed conflicts arising from ethnic tensions, political power struggles, and competition over valuable natural resources like minerals and land [6]. These conflicts have triggered numerous changes in leadership, economic instability, and political unrest. Consequently, the safety of nurses has been significantly impacted by these ongoing regional conflicts [6]. Healthcare workers, including nurses, are often targeted by armed militias, rebel groups, and other factions involved in the conflict, resulting in casualties, injuries, and psychological trauma among the nursing workforce [10]. This insecurity not only endangers the well-being of nurses but also impedes their ability to deliver crucial healthcare services to communities in need. Consequently, many nurses are hesitant to work in conflict-affected regions, exacerbating the shortage of skilled healthcare professionals and further compromising healthcare delivery nationwide. As a result, nurses tend to concentrate in safer regions, such as the urban center of Kinshasa.

Unequal distribution of resources: The DRC healthcare sector demonstrates a concerning lack of prioritization, evident in its meager national healthcare budget. In 2014, this budget stood at 6.9%, declining to 6% by 2017 [11]. Despite reported fluctuations in these percentages over time, the ground reality reflects persistently low funding and a noticeable absence of urgency to address healthcare sector deficiencies. Furthermore, while international aid supplements the national healthcare budget substantially, accounting for nearly 40% of the total, contributions from private funding, non-governmental organizations, and national charitable foundations remain minimal, averaging less than 5% annually [11].

Unfortunately, systemic challenges such as corruption, embezzlement, and resource mismanagement, particularly at the upper echelons of the healthcare system's hierarchical structure, hinder equitable resource distribution of the already meager national healthcare budget [12,13]. Consequently, the second and third tiers of the healthcare pyramid face significant challenges. Thus, despite the WHO recommendations emphasizing the importance of education, regulation, financing, and support to enhance health equity, the DRC continues to struggle to achieve meaningful progress in these areas.

Nurses operate within outdated clinics lacking basic resources like medications and medical supplies. They endure low wages, with a median monthly income of $101 and a maximum of $2908, varying depending on region stability and clinic ownership (private vs. public) [11]. Such imbalances and inequities contribute to a disincentivized workforce and perpetuate an outdated healthcare system, despite attempts at local development initiatives.

Lack of needed advocacy and policy reform: Despite the existence of the National Council of Nurses (NCA), there is a pressing need for significant policy revisions to improve the nursing workforce. Over the years, the association has struggled to effectively advocate for its members amidst longstanding challenges such as a shortage of employment, essential medical resources, and inadequate nurse compensation. This has led to challenges in recruitment, training, and retention of nurses. Wage disparities among nurses and between nurses and other medical professionals, as highlighted by Maria Paola et al., underscore the limited effectiveness of NCA. According to Maria Paola et al, administrative staff receive a monthly income starting at $166, approximately $65 more than that of a nurse [14]. This, along with other indicators, underscores the necessity for a comprehensive policy review and proactive advocacy efforts from the association to tackle the persistent inequities and challenges.

Lack of resources on the health center level: Health centers suffer from inadequate funding, lack of proper equipment, and low wages for nurses. In some cases, the facilities themselves are insufficient for medical practice. Consequently, some nurses have resorted to using their homes as makeshift clinics, deeming them more suitable, including financially, than official medical facilities [15]. However, this practice poses significant risks due to the absence of oversight and unregulated conditions, as these home-based clinics are not subjected to scrutiny. Alarmingly, this practice is well-known to the NCA and other health authorities in the DRC. While the DRC government has previously taken action to dismantle such clinics and prosecute healthcare providers involved, ongoing poverty and social struggles have led to a passive approach, allowing this practice to persist unchecked.

The evidence of healthcare disparities in the DRC is undeniable, and strengthening the nursing workforce can be pivotal in addressing the gap in access to quality care. Improving the nursing workforce will improve healthcare access, reduce disparities in health outcomes, and ultimately enhance population health.

Opportunities for improvement

There is convincing evidence that the healthcare system in the DRC encounters various challenges, such as persistent conflicts and instability in certain regions, scarcity of resources, uneven distribution, ineffective policy and advocacy, and shortages of medical personnel, all of which profoundly affect the nursing workforce. However, amidst these challenges, there are opportunities for innovation and collaboration. Resolving these issues requires a comprehensive approach that addresses systemic challenges from diverse perspectives.

First and foremost, the Congolese government must prioritize peace in the region to enable equitable placement of nurses across the nation. Despite previous efforts, numerous setbacks have nullified any progress toward peace, rendering the current instability unpredictable. A short-term solution could involve collaborating with the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO) to guarantee continuous and comprehensive protection for healthcare workers while long-term peace initiatives are being developed.

Secondly, there is a critical need to reassess and augment the national healthcare budget to meet the current demands. Since 2017, the population of the DRC has surged from less than 85 million to nearly 112 million, amplifying the medical requirements significantly. Therefore, heavy reliance on international aid for such a vital sector of societal sustenance is precarious. Also, the allocation and expenditure of the budget must be rigorously monitored by a local bureau for fraud investigation, in tandem with the criminal division of the justice branch. Both entities can implement quarterly audits of all expenditures and conduct thorough analyses by experts to ensure compliance at every level. This dual oversight system will promote ethical conduct in resource allocation.

Thirdly, there is a necessity for policy reform, with active participation from the nurses' union, to revise policies and incorporate measures that enhance the nursing workforce and remuneration. As outlined by the World Health Organization (2010), salaries play a crucial role in influencing the quantity, distribution, and effectiveness of healthcare workers. Inadequate salaries for certain healthcare professionals can act as a deterrent and contribute to migration to regions where salaries are more lucrative. Moreover, in conflict zones, compensation should reflect the valor of nurses who bravely choose to work in hazardous areas. These measures will bring about substantial transformation in addressing the current challenges faced by the nursing workforce.

Finally, there is a clear path forward, requiring a substantial increase in healthcare funding, particularly directed toward nursing education, training, and retention initiatives. This entails investing in the infrastructure of healthcare facilities to ensure they adequately support nurses in their roles. Furthermore, as highlighted earlier, policies need to be revamped to address wage disparities and ensure equitable compensation for nurses, thus incentivizing them to remain in the profession. Additionally, efforts to enhance the status and recognition of nurses within the healthcare system are imperative for attracting new talent and retaining experienced professionals. Strengthening the capacity of nursing associations and empowering them to advocate effectively for the rights and welfare of nurses will also be pivotal in driving positive change. Lastly, fostering collaboration among government bodies, healthcare institutions, and international partners will be crucial for implementing and sustaining reforms to enhance the nursing workforce throughout the DRC.

Strengthening the nursing workforce stands as a pivotal endeavor in enhancing healthcare accessibility and delivery throughout the DRC. A multitude of systemic challenges, including regional conflicts, resource limitations, ineffective policies and advocacy efforts, and infrastructure deficiencies, profoundly hinder both nurses' ability to deliver quality care and the DRC's capacity to train an adequate number of nurses. Addressing these intricate challenges necessitates collaborative efforts focused on several key areas: establishing regional stability, increasing and judiciously allocating healthcare funding, reforming policies to bolster and incentivize nursing, investing in healthcare infrastructure and fostering nursing capacity, and cultivating partnerships both locally and globally. Prioritizing the nursing workforce is critical for surmounting healthcare disparities, elevating population health outcomes, and advancing progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals in this underserved region.

Conflict of interest

We have collectively declared no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, that might introduce any form of bias or influence into the content presented. We underscore our unwavering dedication to maintaining the integrity and impartiality of the research findings conveyed within this manuscript. We have diligently adhered to ethical standards and guidelines, ensuring that our research process and its outcomes remain free from any potential conflicts that could compromise the objectivity of the work.

- World Health Organization. Nursing and midwifery. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nursing-and-idwifery#:~:text=For%20all%20countries%20to%20reach,delivering%20primary%20and%20community%20care.

- Tamura T, Bapitani DBJ, Kahombo GU, Minagawa Y, Matsuoka S, Oikawa M, Egami Y, Honda M, Nagai M. Comparison of the clinical competency of nurses trained in competency-based and object-based approaches in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: A cross-sectional study. Glob Health Med. 2023 Jun 30;5(3):142-150. doi: 10.35772/ghm.2023.01026. PMID: 37397946; PMCID: PMC10311675.

- World Health Organization. State of the World's Nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs, and leadership. 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279

- World Health Organization. Global standards for the initial education of professional nurses and midwives. 2024.http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44100/ WHO_HRH_HPN_08.6_eng.pdf;jsessionid=020FC14631BA10C09CE5FFC37D1F86C1?sequence=1

- World Health Organization. Global strategic directions for nursing and midwifery 2021-2025. 2024. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344562

- Tshimbombu TN, Kalubye AB, Hoffman C, Kanter JH, Rosseau G, Nteranya DS, Nyalundja AD, Kalala Okito JP. Review of Neurosurgery in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Historical Approach of a Local Context. World Neurosurg. 2022 Nov;167:81-88. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.07.113. Epub 2022 Aug 7. PMID: 35948213.

- Michaels-Strasser S, Thurman PW, Kasongo NM, Kapenda D, Ngulefac J, Lukeni B, Matumaini S, Parmley L, Hughes R, Malele F. Increasing nursing student interest in rural healthcare: lessons from a rural rotation program in Democratic Republic of the Congo. Hum Resour Health. 2021 Apr 20;19(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s12960-021-00598-9. PMID: 33879170; PMCID: PMC8056204.

- Coster S, Watkins M, Norman IJ. What is the impact of professional nursing on patients' outcomes globally? An overview of research evidence. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018 Feb;78:76-83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.10.009. Epub 2017 Oct 19. PMID: 29110907.

- Jarelnape AA, Ali ZT, Fadlala AA, Sagiron EI, Osman AM, Abdelazeem E, Balola H, Albagawi B. The Influence of Nursing Interventions on Patient Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Saudi J Health Syst Res. 2023; https://doi.org/10.1159/000534482

- Makali SL, Lembebu JC, Boroto R, Zalinga CC, Bugugu D, Lurhangire E, Rosine B, Chimanuka C, Mwene-Batu P, Molima C, Mendoza JR, Ferrari G, Merten S, Bisimwa G. Violence against health care workers in a crisis context: a mixed cross-sectional study in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Confl Health. 2023 Oct 3;17(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s13031-023-00541-w. PMID: 37789323; PMCID: PMC10546691.

- Mushagalusa CR, Mayeri DG, Kasongo B, Cikomola A, Makali SL, Ngaboyeka A, Chishagala L, Mwembo A, Mukalay A, Bisimwa GB. Profile of health care workers in a context of instability: a cross-sectional study of four rural health zones in eastern DR Congo (lessons learned). Hum Resour Health. 2023 Apr 20;21(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12960-023-00816-6. PMID: 37081428; PMCID: PMC10120134.

- Bujakera S, Holland H. Congo Virus Funds Embezzled by ‘Mafia Network,’ Says Deputy Minister. 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-congo-corruption-idUSKBN249225. Accessed January 28, 2024.

- Juma CA, Mushabaa NK, Abdu Salam F, Ahmadi A, Lucero-Prisno DE III. COVID-19: The Current Situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2020;103(6):2168-2170. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-1169

- Bertone MP, Lurton G, Mutombo PB. Investigating the remuneration of health workers in the DR Congo: implications for the health workforce and the health system in a fragile setting. Health Policy Plan. 2016 Nov;31(9):1143-51. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv131. Epub 2016 Jan 11. PMID: 26758540.

- In DRC, unlicensed nurses make house calls for Cheap. Global Press Journal. 2022. https://globalpressjournal.com/africa/democratic-republic-of-congo/hospitals-expensive-people-drc-call-nurses-homes-instead/